Research Article

Dominik Ostrowski, Dorota Banaszewska , Barbara Biesiada-Drzazga

Institute of Bioengineering and Animal Breeding, Siedlce University of Natural Sciences and Humanities, 08-110 Siedlce, B. Prusa 14, Poland

Abstract. The aim of the study was to assess breeding of zebra finches kept in a flock in an amateur indoor aviary. The research was carried out at an amateur breeding facility in the Masovian Voivodeship in 2014–2018. The subject of the study was 5 pairs of zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) kept in an indoor aviary. Analysis of breeding was based on the following parameters: number of eggs laid, number of chicks hatched, and number of chicks reared from two broods each year. The reproductive parameters of the zebra finch pairs were varied. There were differences between individual pairs of birds for both the number of eggs laid per clutch and the number of chicks reared. Most of the zebra finch pairs had very good reproductive parameters; only a pair consisting of two albino individuals did not rear any offspring in any of the breeding seasons.

Keywords: zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata), reproductive parameters

The zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) (Fig. 1) is one of the most popular and commonly raised birds. They are small (10–12 cm) [Jabłoński 1998Jabłoński, K.M. (1998). Zeberki i mewki [Zebra finches and society finches]. Agencja Wydawnicza Egros, Warszawa [in Polish].], very active and energetic, curious, and very colourful [Kruszewicz 2000Kruszewicz, A.G. (2000). Hodowla ptaków ozdobnych [Breeding ornamental birds]. MULTICO Oficyna Wydawnicza, Warszawa [in Polish]., 2002Kruszewicz, A.G. (2002). Tajniki z życia zeberek [Secrets of the life of zebra finches]. Woliera, 1, 28–30 [in Polish].]. In natural conditions, zebra finches colonize Australia and the Lesser Sunda Islands. They usually inhabit dry grasslands or open areas with sparse trees [Chvapil 1985Chvapil, S. (1985). Ptaki ozdobne [Ornamental birds]. PWRiL, Warszawa [in Polish].]. They need close proximity to water bodies. As their diet consists predominantly of dry grass seeds, these birds must drink regularly. Zebra finches are very social birds [Poot et al. 2012Poot, H., ter Maat A., Trost L., Schwabl, I., Jansen, R.F., Gahr, M. (2012). Behavioural and physiological effects of population density on domesticated Zebra Finches (Taeniopygia guttata) held in aviaries. Physiol. Behav., 105(3), 821–828. https://doi.org/doi.org/10.1016/Fj.physbeh.2011.10.013.] and often form large flocks numbering 10–100 individuals. During the breeding season, however, the large flocks break up into smaller colonies, find a suitable tree, and breed there. A single tree provides a nesting place for several pairs [Hanzak 1976Hanzak, J. (1976). Wielki atlas ptaków [Great atlas of birds]. PWRiL, Warszawa [in Polish]., Zientek 2014Zientek, H. (2014). Encyklopedia ptaki ozdobne [Encyclopaedia. Ornamental birds]. Wydaw. Dragon, Bielsko-Biała [in Polish].]. Zebra finches are monogamous birds. They form pairs over a few days, creating a bond that lasts for the rest of their lives, except for the egg incubation period [Tynes 2010Tynes, V. (2010). Behavior of exotic pets (p. 13). Chichester, West Sussex: Blackwell Pub.]. The zebra finch has pronounced sexual dimorphism [Alderton 1994Alderton, D. (1994). Ty i twoje ptaki [You and your birds]. Wydaw. MUZA, Warszawa [in Polish].

]. Males have russet orange cheeks and chestnut feathers with spots under the wings. Females do not have these features. In both sexes the upper part of the body is brownish, the head is grey, the underside of the body is white, and the breast is lightly striped and separated from the abdomen by a clear black line. The tail is adorned with transverse black and white stripes. The beak is short, strong, and red. There is a vertical black line under the eye [Jabłoński and Lubik 2008Jabłoński, K.M., Lubik, P. (2008). Zeberki. Hodowla i mutacje [Zebra finches. Breeding and mutations]. Agencja Wydawnicza Egros, Warszawa [in Polish]., Korbel 2009aKorbel, D. (2009a). Mutacje zeberek. cz. 1 [Zebra finch mutations. Part 1], Fauna & Flora, 7, 9 [in Polish]., 2009bKorbel, D. (2009b). Mutacje zeberek. cz. 2 [Zebra finch mutations. Part 2], Fauna & Flora, 8, 7 [in Polish]., 2009cKorbel, D. (2009c). Mutacje zeberek cz. 3 [Zebra finch mutations. Part 3], Fauna & Flora, 9, 17 [in Polish]., Ślesicki 2012aŚlesicki, D. (2012a). Standard i mutacje barwne zeberek [Zebra finch standard and colour mutations]. Nowa Exota, 4, 20–23 [in Polish]., 2012bŚlesicki, D. (2012b). Standard i mutacje barwne zeberek [Zebra finch standard and colour mutations]. Nowa Exota, 5, 17–19 [in Polish]., 2013aŚlesicki, D. (2013a). Standard i mutacje barwne zeberek [Zebra finch standard and colour mutations]. Nowa Exota, 3, 16–18 [in Polish]., 2013bŚlesicki, D. (2013b). Standard i mutacje barwne zeberek [Zebra finch standard and colour mutations]. Nowa Exota, 6, 27–28 [in Polish]., 2014Ślesicki, D. (2014). Standard i mutacje barwne zeberek [Zebra finch standard and colour mutations]. Nowa Exota, 1, 24–25 [in Polish].]. Breeding usually takes place in the rainy season, but can begin after any major rain. In Australia, the breeding season is in spring and autumn [Immelmann 1982Immelmann, K. (1982). Australian Finches in Bush and Aviary. Angus & Robertson, Sydney.]. Birds that inhabit the south of the continent breed more regularly. Zebra finches nest in tree hollows, at a considerable height of 2–3 m, or in shrubs. Females lay from 2 to 8 eggs, but usually 3 or 4 [Moghal and Farooqui 2017Moghal, M.M., Farooqui, M. (2017). Behavior of Domesticated Zebra Finches (Taeniopygia guttata) in Colony and in Individual Cage and Its Effect on Their Breeding. Saudi J. Life Sci., 2, 5, 155–157.]. They do not begin to incubate them until the third egg has been laid. It is incubated by both birds of the pair, but the females spend more time in the nest [Case 1986Case, V.M. (1986). Breeding cycle aggression in domesticated zebra finches (Poephila guttata). Aggr. Behav., 12, 337–348. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-2337(1986)12:53.0.co;2-f., Samuel 2012Samuel, J. (2012). Keeping Finches, Doves and Quails. Springwood Emedia.]. The young hatch after about 12–14 days [Jabłoński 1998Jabłoński, K.M. (1998). Zeberki i mewki [Zebra finches and society finches]. Agencja Wydawnicza Egros, Warszawa [in Polish].]. Young chicks are about 3 cm long and covered with white down [Boruszewska et al. 2007Boruszewska, K., Witkowski, A., Jaszczak, K. (2007). Selected growth and development traits of the Zebra Finch (Poephila guttata) nestlings in amateur breeding. Anim. Sci. Pap. Rep., 25, 2, 97–110.]. The young birds begin to leave the nest about 17 days after hatching, with a mass exodus from the nests at about 21 days after hatching. Most birds reach the body weight characteristic of adults in their fourth week of life [Boruszewska et al. 2007Boruszewska, K., Witkowski, A., Jaszczak, K. (2007). Selected growth and development traits of the Zebra Finch (Poephila guttata) nestlings in amateur breeding. Anim. Sci. Pap. Rep., 25, 2, 97–110.]. Young birds begin to fledge at 8 weeks, and between 12 and 14 weeks have the plumage of an adult bird [Boruszewska 2003Boruszewska, K. (2003). Pisklęta zeberki australijskiej [Zebra finch chicks]. Woliera, 4, 46–47 [in Polish]., Zientek 2004Zientek, H. (2004). Lęgi zeberek – najczęstsze problemy [Zebra finch breeding – the most common problems]. Woliera, 9, 34–40 [in Polish]., Boruszewska et al. 2007Boruszewska, K., Witkowski, A., Jaszczak, K. (2007). Selected growth and development traits of the Zebra Finch (Poephila guttata) nestlings in amateur breeding. Anim. Sci. Pap. Rep., 25, 2, 97–110., Kuziemkowski 2017Kuziemkowski, T. (2017). Niepowodzenia lęgów [Breeding failure]. Fauna & Flora, 5, 10 [in Polish].].

The aim of the study was to assess the breeding of zebra finches kept in a flock in an amateur indoor aviary.

The research was carried out at an amateur breeding facility in the Masovian Voivodeship in the years 2014–2018. The birds were bred in an indoor aviary with dimensions of 3.2×1.5×2.4 m (L×W×H). The aviary was equipped with feeders, water dispensers and baths. In addition, the bottom of the cage was sprinkled with fine sand, coconut fibres and bark to provide the birds with access to gastroliths and the opportunity to search the bottom for the food that had fallen out of the feeders. The birds were fed a mixture of small grains intended for finches, which contained two kinds of millet (yellow and red), canary grass, niger seed, agrimony, husked oats and seeds of weeds and grasses. The birds had constant access to fruits and vegetables (grated apple, carrot and beetroot) and to herbs (chickweed, ribwort plantain and dandelion). In addition, during the breeding period the birds’ diet was supplemented with germinated millet, an egg mixture, mealworm larvae, and cuttlefish. Half-open nest boxes with dimensions of 15×15×15 m were used for breeding. The observations were carried out on 5 pairs of birds that reared two broods per year. At the beginning of March, the birds intended for breeding were placed in the aviary at the same time. After about 9 days pairs were formed, which were then observed. They were provided with 12 half-open nest boxes in order to avoid conflicts during the choice of a nesting site. The zebra finch pairs displayed a number of interesting mating behaviours, which lasted about a week before the first egg was laid. Because the birds were kept in a small colony, they could be stimulated to breed simultaneously. This resulted in nearly simultaneous egg-laying by the females, observed as early as the fourth week of March. Both birds in the pair incubated the eggs, sharing the duty in turns. The first chicks hatched about 2 weeks after the first egg was laid. Newly-hatched zebra finches are blind, naked and incapable, and thus completely dependent on the adult birds that tend to them with care, allowing them to grow very rapidly. After 3 weeks, the young left their nests, but they were additionally fed by their parents for about two weeks. After this period, the young were separated from the adult birds, because the males were becoming aggressive towards them. This also stimulated the females to breed again. The second breeding period immediately followed the first and proceeded in the same manner. When the young from the second brood had left the nests, they were also separated from the adult birds, and all nest boxes were removed from the aviary so as not to stimulate the birds to further breeding. The egg mixture was also eliminated from the birds’ diet. After the two breeding periods had been completed, the aviary was divided into two parts by a mesh partition and the adult males were separated from the females to allow the birds to regain their condition after breeding and to prevent further breeding. Owing to constant eye contact, the birds did not change partners and carried out subsequent breeding in the same configurations. In the part of the aviary with females, isolated scattered eggs were occasionally found during inspection and cleaning; these were immediately removed. Analysis of breeding was based on the following parameters: number of eggs laid, number of chicks hatched, and number of chicks reared from 2 broods per year by each pair. Statistical analysis of the results was performed by the chi square test (χ2) at P ≤ 0.05.

The zebra finch reproduces very well in a group, provided that there are more nest boxes than males. When the birds are ready to breed, the male begins his courtship display. It hops and steps around the female while singing a mating song that resembles the sound of a children’s toy horn, whereas outside the breeding period its song is usually a short nasal trill. When the female accepts the courtship of a potential partner, she squats, vibrates her tail and chirps. This is a signal for the male that the female is ready to mate. The pair copulates repeatedly throughout the day. To build a trough-shaped nest, zebra finches use hay, coconut fibres and feathers, mainly white ones, which the male delivers to the nest even when the female is incubating the eggs. During our observations, the females laid 3 to 6 eggs depending on their age. The female and the male incubate the eggs in turns. The incubation period is about 14 days. The chicks stay in the nest less than 3 weeks, and 5 weeks after hatching they are fully independent and ready to be separated from their parents. During the breeding period, no irregularities were found in the breeding of the zebra finches and no significant obstacles preventing rearing of the young were encountered. The only hindrance to normal breeding of the zebra finches was the colour of the plumage. The pairing of albino individuals resulted in the death of embryos in the eggs or hatching of underdeveloped and crippled chicks, which soon died due to congenital malformations or of hypothermia, as they were rejected by the adults. This was because the individuals carried recessive albinism genes, which in combination were also lethal genes causing the death of the chicks.

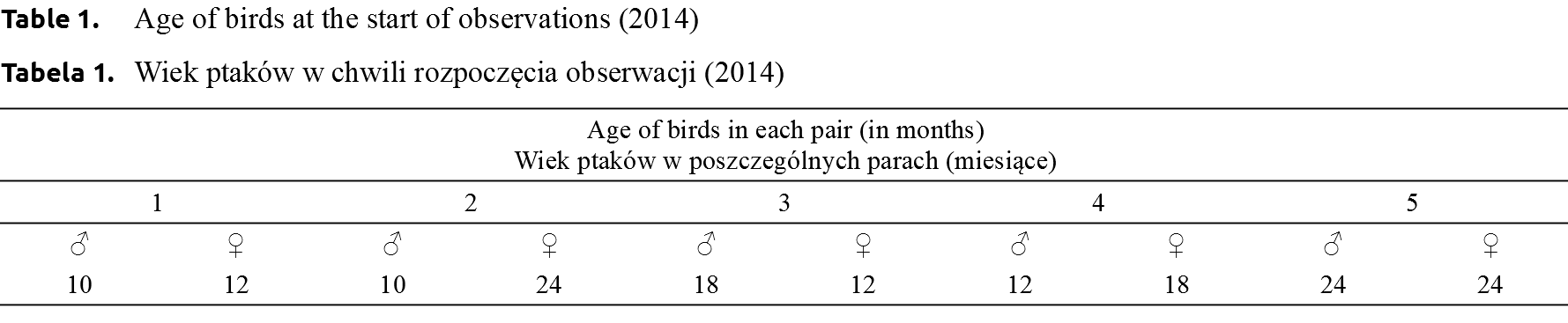

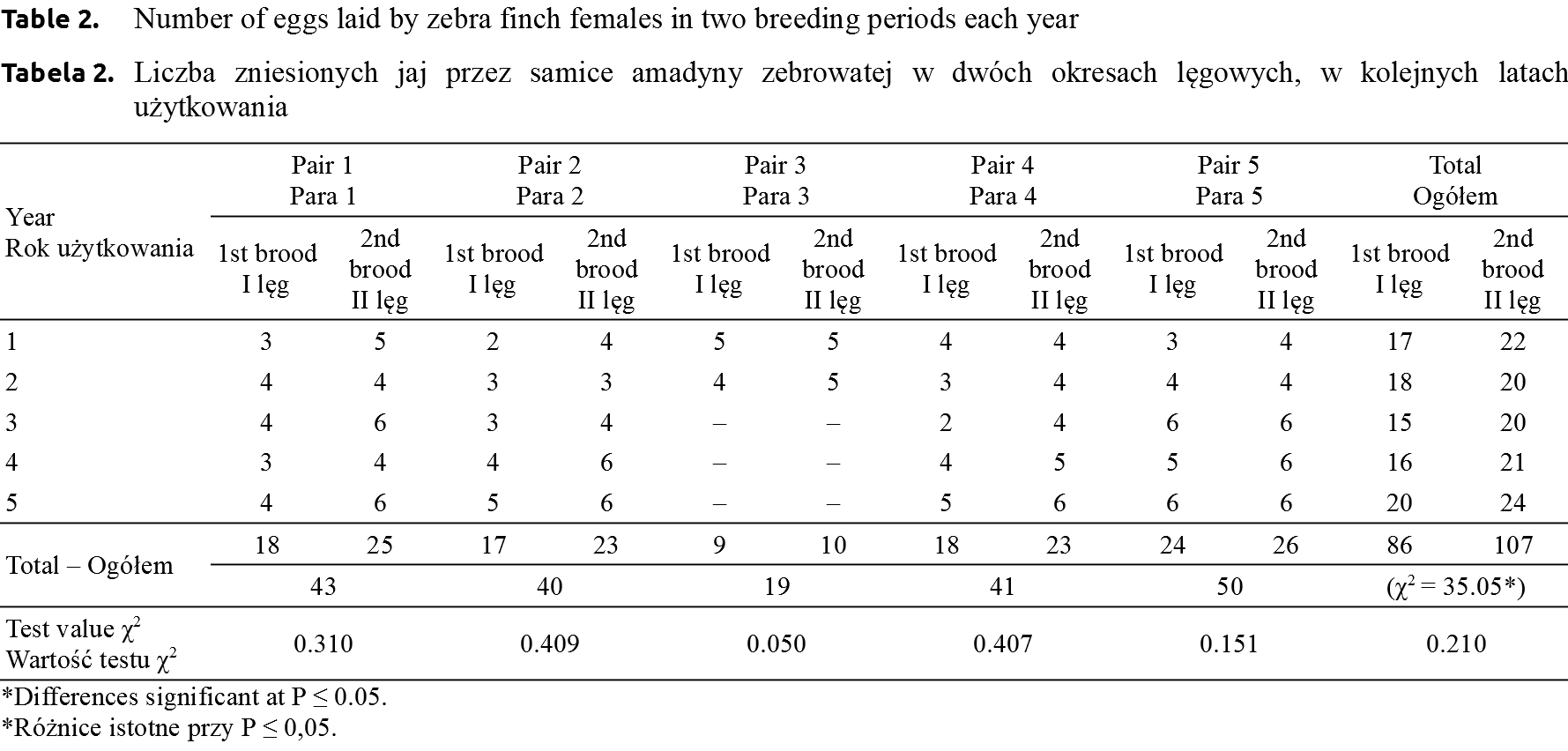

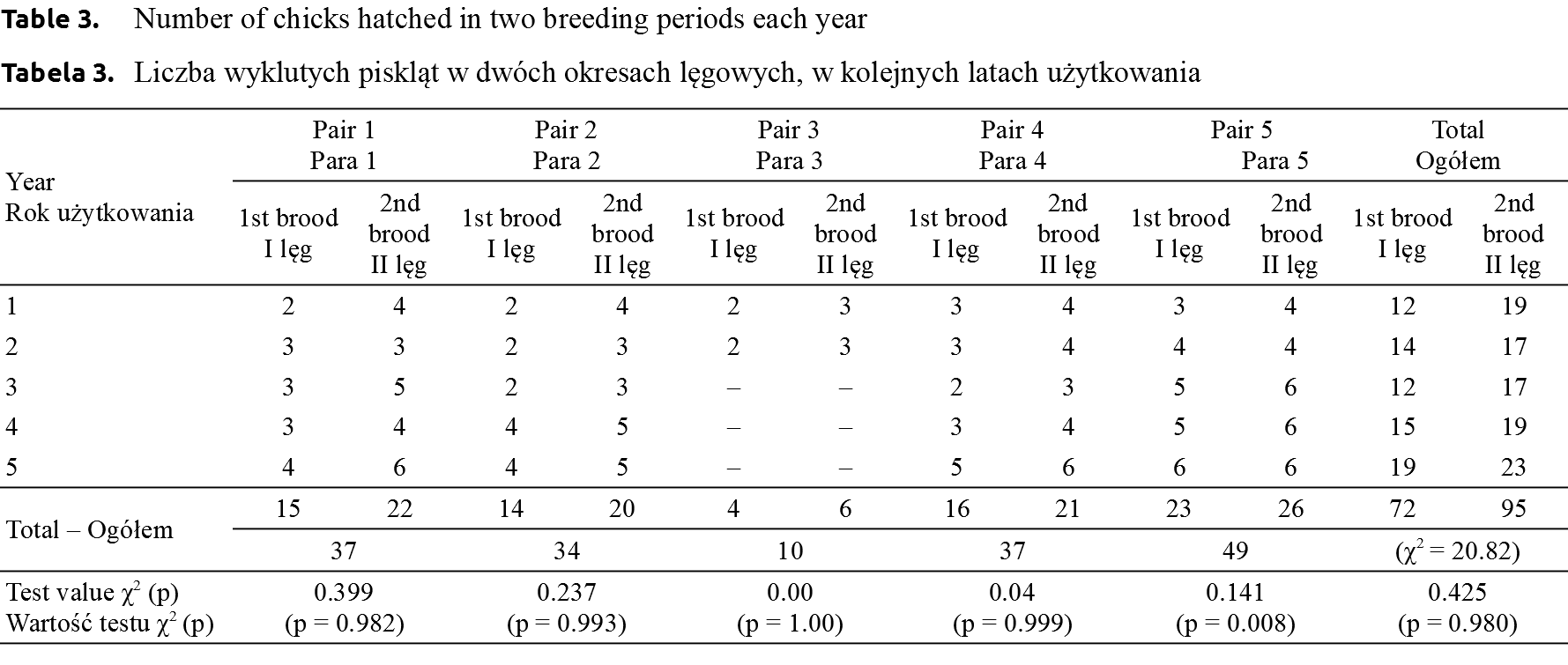

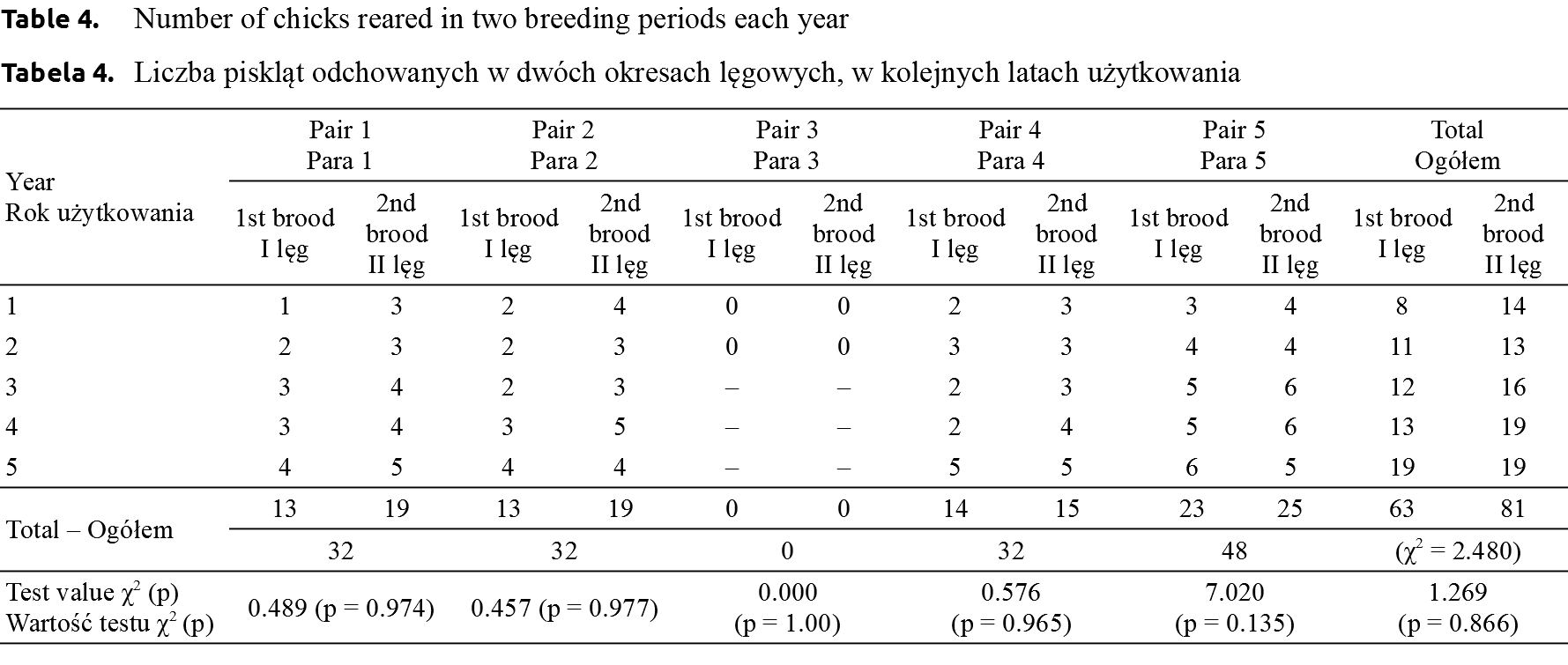

Table 2 shows the number of eggs laid by female zebra finches each year and in two breeding periods per year. Female zebra finches laid from 2 to 6 eggs in one breeding season. The table shows that the number of eggs laid did not differ between broods. In each case, however, the females laid 1–2 more eggs in the second breeding period. Significant differences were found between the numbers of eggs laid by the females of individual pairs (χ2 = 35.05). The most eggs were laid by the female from pair 5. Over 5 years the female of this pair laid 50 eggs altogether, of which only one was unfertilized (Table 3), and only one chick died after hatching (Table 4). However, these differences were not statistically confirmed by the chi square test, in which values of 20.82 and 2.48, respectively, were obtained. This pair reared a total of 48 healthy chicks, which was 16 more than pairs 1 and 2, and 19 more than pair 4. Pairs 1, 2 and 4 reared similar numbers of healthy chicks (29–32). The most deaths were observed for pair 3, a pair of albino birds. In this case, of 19 eggs laid, only 10 were fertilized, and none of the hatched chicks survived to the 5th day, so that no chicks were reared by this pair of zebra finches. The main cause of death in the chicks was anatomical defects. The chicks were hatched lame and weak or died while still in the egg. This was probably because the birds were closely related, as well as due to the white (recessive) colour of the plumage, which passed on to the young by both parents results in lethality.

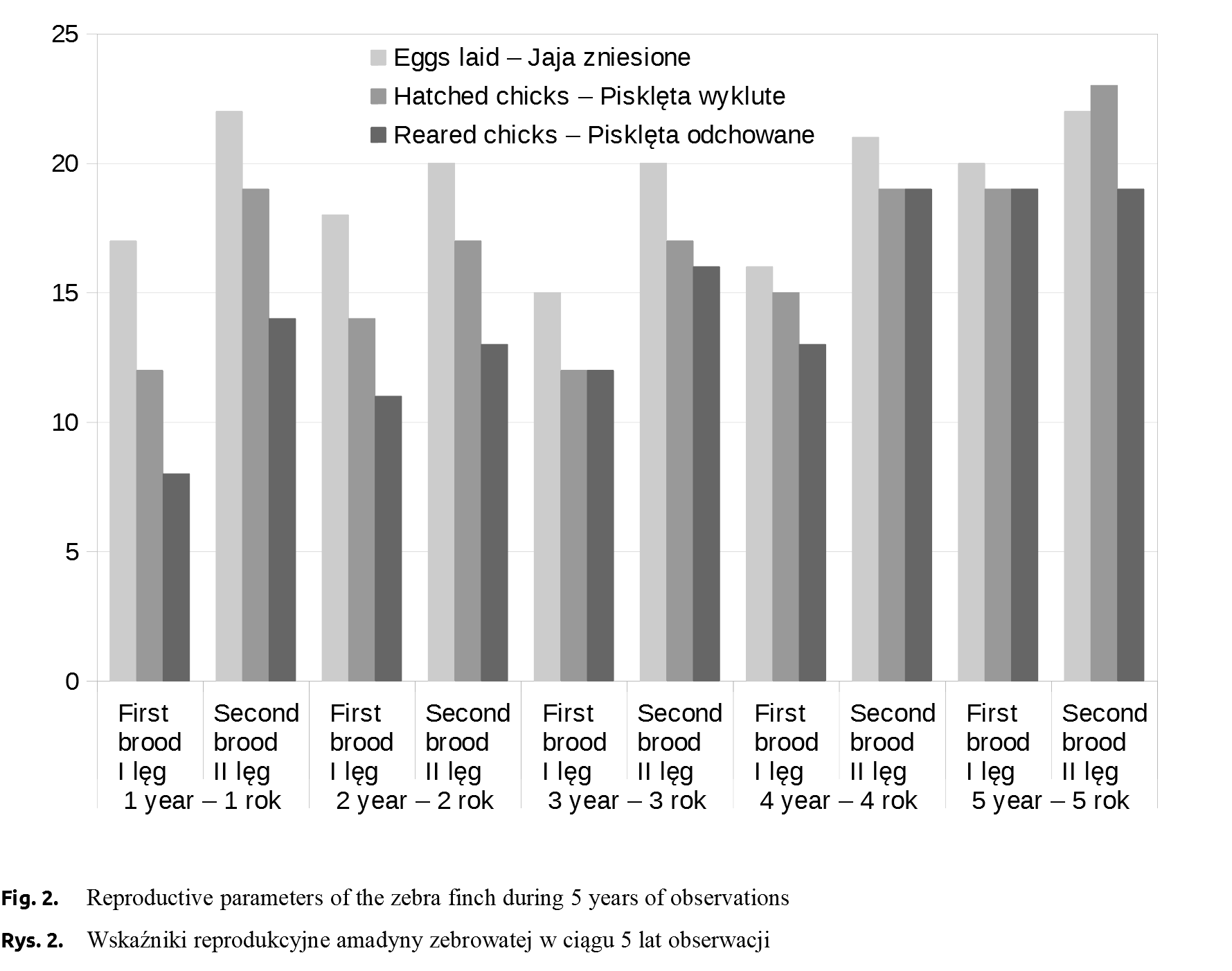

\hyperref[fig2]{Figure 2} shows that irrespective of the age of birds, in each case better reproductive parameters were observed in the second breeding period. However, the best results were obtained in the fifth year of observation, which may have been linked to their age and the experience acquired during previous breeding periods.

The zebra finch achieves sexual maturity at 4 months of age. Female zebra finches usually lay 4 to 6 white eggs weighing about 1 g or slightly less [Jabłoński 1998Jabłoński, K.M. (1998). Zeberki i mewki [Zebra finches and society finches]. Agencja Wydawnicza Egros, Warszawa [in Polish].]. According to Sossinka [1980Sossinka, R. (1980). Reproductive strategies of estrildid finches in different climatic zones of the tropics: gonadal maturation. Proceedings of XVII International Ornithological Congress, 5-11.06.1978, Berlin, 493-497.], zebra finches reach sexual maturity as early as 2–2.5 months, with females maturing a bit later. In observations by Moghal and Farooqui [2017Moghal, M.M., Farooqui, M. (2017). Behavior of Domesticated Zebra Finches (Taeniopygia guttata) in Colony and in Individual Cage and Its Effect on Their Breeding. Saudi J. Life Sci., 2, 5, 155–157.], the females of zebra finch pairs laid 3–4 eggs, and the breeding results varied depending on the conditions they were raised in. Reproductive success was observed in pairs that were kept in separate cages, which eliminated the desire to defend their nests and interfere with one another. These behaviours were observed when several pairs were kept in one cage, which negatively influenced breeding. This was not confirmed by our research, as the pairs were kept in one aviary and no aggressive behaviour was observed. According to Gorman et al. [2005Gorman, H.E., Orr, K.J., Adam, A., Nager, R.G. (2005). Effects of Incubation Conditions and Offspring Sex on Emryonic Development and Survival in the Zebra Finch (Taeniopygia guttata). The Auk, 122, 4, 1239–1248. https://doi.org/10.1642/0004-8038(2005)122[1239:eoicao]2.0.co;2.], in addition to the quality of the eggs themselves, the condition of the hatched offspring and the success of the brood can also be influenced by incubation behaviour. The authors observed lower embryo mortality in eggs incubated by parents with better health. In addition, the chicks incubated by the parents in better condition weighed more than the chicks incubated by parents whose state of health was poorer. Moghal and Farooqui [2017Moghal, M.M., Farooqui, M. (2017). Behavior of Domesticated Zebra Finches (Taeniopygia guttata) in Colony and in Individual Cage and Its Effect on Their Breeding. Saudi J. Life Sci., 2, 5, 155–157.] observed that dominant pairs achieved greater reproductive success. There were also differences in the body weight of the chicks, with newly hatched females weighing more than males [Gorman et al. 2005Gorman, H.E., Orr, K.J., Adam, A., Nager, R.G. (2005). Effects of Incubation Conditions and Offspring Sex on Emryonic Development and Survival in the Zebra Finch (Taeniopygia guttata). The Auk, 122, 4, 1239–1248. https://doi.org/10.1642/0004-8038(2005)122[1239:eoicao]2.0.co;2.]. Increased aggression may be observed during the zebra finch breeding season, more so in males than in females, due to the need to protect the nesting sites. Furthermore, each pair attempts to keep an appropriate distance from other members of the colony [Case 1986Case, V.M. (1986). Breeding cycle aggression in domesticated zebra finches (Poephila guttata). Aggr. Behav., 12, 337–348. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-2337(1986)12:53.0.co;2-f., Tynes 2010Tynes, V. (2010). Behavior of exotic pets (p. 13). Chichester, West Sussex: Blackwell Pub.]. However, aggression is associated with rivalry within the same gender. Males are more aggressive towards males and females towards females [Pfaff 2002Pfaff, D. (2002). Hormones, brain, and behavior. Amsterdam: Academic Press, 4, 243.]. A hierarchy is also established in the flock, resulting in the formation of a dominant pair and subordinate pairs [Favati et al. 2014Favati, A., Leimar, O., Lovlie, H. (2014). Personality Predicts Social Dominance in Male Domestic Fowl. PLOS ONE, 9(7), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0103535.].

According to Zann and Rossetto [1991Zann, R.A., Rossetto, M. (1991). Zebra finch incubation: brood patch, egg temperature and thermal properties of the nest. Emu, 91, 107–120.] and Zann [1996Zann, R.A. (1996). The Zebra Finch. A Synthesis of Field and Laboratory studies. Oxford University Press, Oxford.], the zebra finch begins incubation after laying the first egg, which leads to asynchronous hatching and gives a significant advantage to earlier chicks in competition for food provided by their parents [Glassey and Forbes 2002Glassey, B., Forbes, S. (2002). Begging and Asymmetric Nestling Competition. In: Wright J., Leonard M.L. (eds) The Evolution of Begging. Springer, Dordrecht, 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-306-47660-6_14.]. Hatching asynchrony has been shown to be more common in aviaries than in the wild [Amundson and Slagsvold 1991Amundson, T., Slagsvold, T. (1991). Hatching asynchrony: facilitating adaptive or maladaptive brood reduction. Acta XX Congressus Internationalis Ornithologici, 1707–1719., Zann 1996Zann, R.A. (1996). The Zebra Finch. A Synthesis of Field and Laboratory studies. Oxford University Press, Oxford.]. Research by many scientists indicates that chick development can be controlled by parents in various ways. There have been cases showing that the order in which eggs are laid is correlated with their size, which allows a ranking to be established among the chicks, increasing the chances of survival of selected chicks [Adkins-Regan et al. 2013Adkins-Regan, E., Banerjee, S.B., Correa, S.M., Schweitzer, C. (2013). Maternal effects in quail and zebra finches: Behavior and hormones. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol., 190, 34–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2013.03.002., Deeming and Reynolds 2015Deeming, D.C., Reynolds, S.J. (2015). Nests, eggs, and incubation: new ideas about avian reproduction. Oxford University Press, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1642/auk-16-185.1.]. The first three days are decisive for the survival of young chicks [Boruszewska et al. 2007Boruszewska, K., Witkowski, A., Jaszczak, K. (2007). Selected growth and development traits of the Zebra Finch (Poephila guttata) nestlings in amateur breeding. Anim. Sci. Pap. Rep., 25, 2, 97–110.]. The parents do not begin to feed the chicks until the day after hatching [Zann 1996Zann, R.A. (1996). The Zebra Finch. A Synthesis of Field and Laboratory studies. Oxford University Press, Oxford.]. Chicks that want to draw attention to themselves move their head and neck and emit their own characteristic sounds [Ferens and Wojtusiak 1960Ferens, B., Wojtusiak, R.J. (1960). Ornitologia Ogólna [General Ornithology]. PWN, Warszawa [in Polish].]. According to Ikebuchi et al. [2017Ikebuchi, M., Okanoya, K., Hasegawa, T., Bischof, H.J. (2017). Chick Development and Asynchroneous Hatching in the Zebra Finch (Taeniopygia guttata castanotis). Zoolog. Sci., 34(5), 369–376. https://doi.org/10.2108/zs160205.], the mortality rate of chicks depends on their birth weight. The authors noted the majority of deaths before the 7th day of life, and the rest between 15 and 20 days of age. The chicks that died had a lower birth weight than the hatchlings that survived. However, observations by Ikebuchi et al. [2017Ikebuchi, M., Okanoya, K., Hasegawa, T., Bischof, H.J. (2017). Chick Development and Asynchroneous Hatching in the Zebra Finch (Taeniopygia guttata castanotis). Zoolog. Sci., 34(5), 369–376. https://doi.org/10.2108/zs160205.] show that the differences in weight do not lead to discrimination by the parents, due to the camouflage effect of the down, which makes it almost impossible to distinguish the younger birds from older hatchlings when they are all in the nest. However, differences in the weight of the hatchlings have a lasting effect, and this disproportion persists in adult birds, which may give heavier birds an advantage, e.g. in finding a partner and in ultimate reproductive success [Haywood and Perrins 1992Haywood, S., Perrins, C.M. (1992). Is clutch size in birds affected by environmental conditions during growth? P. Roy. Soc. Lond. B Bio., 249, 195–197. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1992.0103., Ikebuchi and Okanoya 2006Ikebuchi, M., Okanoya, K. (2006). Growth of pair bonding in zebra finches: physical and social factors. Ornithol. Sci., 5, 65–75. https://doi.org/10.2326/osj.5.65.]. Chick rearing results and survival may also be affected by the beak, its size and colour, and the width of the opening during begging [Ikebuchi et al. 2017Ikebuchi, M., Okanoya, K., Hasegawa, T., Bischof, H.J. (2017). Chick Development and Asynchroneous Hatching in the Zebra Finch (Taeniopygia guttata castanotis). Zoolog. Sci., 34(5), 369–376. https://doi.org/10.2108/zs160205.].

According to Golüke et al. [2016Golüke, S., Dörrenberg, S., Krause, E.T., Caspers, B.A. (2016). Female Zebra Finches Smell Their Eggs. PLoS One, 11(5), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155513.], the olfactory abilities of the zebra finch are noteworthy. Near the end of the incubation period (at about 10 days), female birds of this species are able to distinguish their own eggs from those placed in the nest by other birds. The females were observed to devote more time to them and stay closer to them. The tenth day of incubation, when the female is able to recognize her own eggs, is early enough that the chicks are not yet hatched, and the parents can devote the time and energy required to incubate and rear them to their own offspring [Monaghan and Nager 1997Monaghan, P., Nager, R.G. (1997). Why don’t birds lay more eggs? Trends Ecol. Evol., 12, 270–274.]. It is also believed that during embryonic development eggs emit volatile compounds that depend on the sex of the embryo [Webster et al. 2015Webster, B., Hayes, W., Pike, T.W. (2015). Avian Egg Odour Encodes Information on Embryo Sex, Fertility and Development. PloS ONE, 10, 1–10.], which probably allows females to identify the sex of the chicks. Observations by Wada et al. [2018Wada, H., Kriengwatana, B.P., Steury, T.D., MacDougall-Shackleton, S.A. (2018). Incubation temperature influences sex ratio and offspring’s body composition in Zebra Finches (Taeniopygia guttata). Can. J. Zool., 96(9), 1010–1015.] indicate that incubation temperature can potentially affect the sex, phenotype, body condition and survival of the offspring. Birds can stimulate these conditions by varying the time spent sitting on the eggs, adjusting it to the ambient temperature. Boruszewska et al. [2007Boruszewska, K., Witkowski, A., Jaszczak, K. (2007). Selected growth and development traits of the Zebra Finch (Poephila guttata) nestlings in amateur breeding. Anim. Sci. Pap. Rep., 25, 2, 97–110.] have obtained fairly low hatching results, at a level of 34%, which the authors suppose may have been linked to environmental conditions and weather, and above all to rainfall. In addition, chicks living in captivity have been shown to have faster rates of growth and plumage development than chicks under natural conditions, perhaps due to the increased availability of food [Boruszewska et al. 2007Boruszewska, K., Witkowski, A., Jaszczak, K. (2007). Selected growth and development traits of the Zebra Finch (Poephila guttata) nestlings in amateur breeding. Anim. Sci. Pap. Rep., 25, 2, 97–110.]. Research by many authors shows that birds can control the sex of their offspring depending on the prevailing environmental conditions [Sheldon et al. 1999Sheldon, B.C., Andersson, S., Griffith, S.C., Ornborg, J., Sendecka, J. (1999). Ultraviolet colour variation influences blue tit sex ratios. Nature, 402, 874–877.] and availability of food resources [Bradbury and Blakey 1998Bradbury, R.B., Blakey, J.K. (1998). Diet, maternal condition, and off spring sex ratio in the zebra finch, Poephila guttata. P. Roy. Soc. Lond., B, 265, 895–899. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1998.0375., Kilner 1998Kilner, R. (1998). Primary and secondary sex ratio manipulation by zebra finches. Animal Behaviour, 56, 155–164. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.1998.0775., Rutkowska and Cichoń 2002Rutkowska, J., Cichoń, M. (2002). Maternal investment during egg laying and offspring sex: an experimental study of zebra finches. Anim. Behav., 64, 817–822. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.2002.1973.]. This dependence was evident in breeding when food availability was limited; the proportion of males was higher, because females are more vulnerable to malnutrition and have higher mortality rates both as chicks and as adults [de Kogel 1997de Kogel, C.H. (1997). Long-term effects of brood size manipulation on morphological development and sex-specific mortality of offspring. J. Animal Ecol., 66, 167–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/6019., Kilner 1998Kilner, R. (1998). Primary and secondary sex ratio manipulation by zebra finches. Animal Behaviour, 56, 155–164. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.1998.0775.]. Male chicks were found to be heavier than females [Rutkowska and Cichoń 2002Rutkowska, J., Cichoń, M. (2002). Maternal investment during egg laying and offspring sex: an experimental study of zebra finches. Anim. Behav., 64, 817–822. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.2002.1973.], but nearly all female chicks hatched, while hatching of males was less successful. Kilner [1998Kilner, R. (1998). Primary and secondary sex ratio manipulation by zebra finches. Animal Behaviour, 56, 155–164. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.1998.0775.] speculates that eggs containing female embryos are laid earlier because females are more vulnerable than males, and by hatching earlier they can better compete for food. Research by Williams and Christians [2003Williams, T.D., Christians, J.K. (2003). Experimental dissociation of the effects of diet, age and breeding experience on primary reproductive effort in zebra finches Taeniopygia guttata. Journal of Avian Biology, 34, 379–386.] found that the weight of eggs was not affected by the age of birds, but was dependent on the birds’ diet. This has also been confirmed in studies by other authors [Selman and Houston 1996Selman, R.G., Houston, D.C. (1996). The effect of prebreeding diet on reproductive investment in birds. Proc. R. Soc. Lond., B, 263, 1585–1588., Williams 1996Williams, T.D. (1996). Variation in reproductive effort in female zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) in relation to nutrient-specific dietary supplements during egg laying. Physiol. Zool., 69, 1255–1275.]. Older birds have been shown to have shorter intervals between breeding periods [Williams and Christians 2003Williams, T.D., Christians, J.K. (2003). Experimental dissociation of the effects of diet, age and breeding experience on primary reproductive effort in zebra finches Taeniopygia guttata. Journal of Avian Biology, 34, 379–386.], and the number of eggs laid increased with age, but only in the case of birds receiving a low-quality diet.

Most of the zebra finch pairs observed had very good reproductive parameters; only a pair of albino individuals did not successfully rear any offspring in any of the breeding seasons. The reproductive parameters for the second brood (II) were higher than for the first brood (I) in the entire study period. The present study provides the basis for further observations of the breeding and incubation behaviour of zebra finches and may constitute comparative material for this type of research conducted in nature.

Received: 20 Mar 2019

Accepted: 15 Apr 2019

Published online: 17 Jul 2019

Accesses: 1013

Ostrowski, D., Banaszewska, D., Biesiada-Drzazga, B., (2019). Assessment of reproductive parameters of privately bred zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata). Acta Sci. Pol. Zootechnica, 18(1), 33–40. DOI: 10.21005/asp.2019.18.1.05.